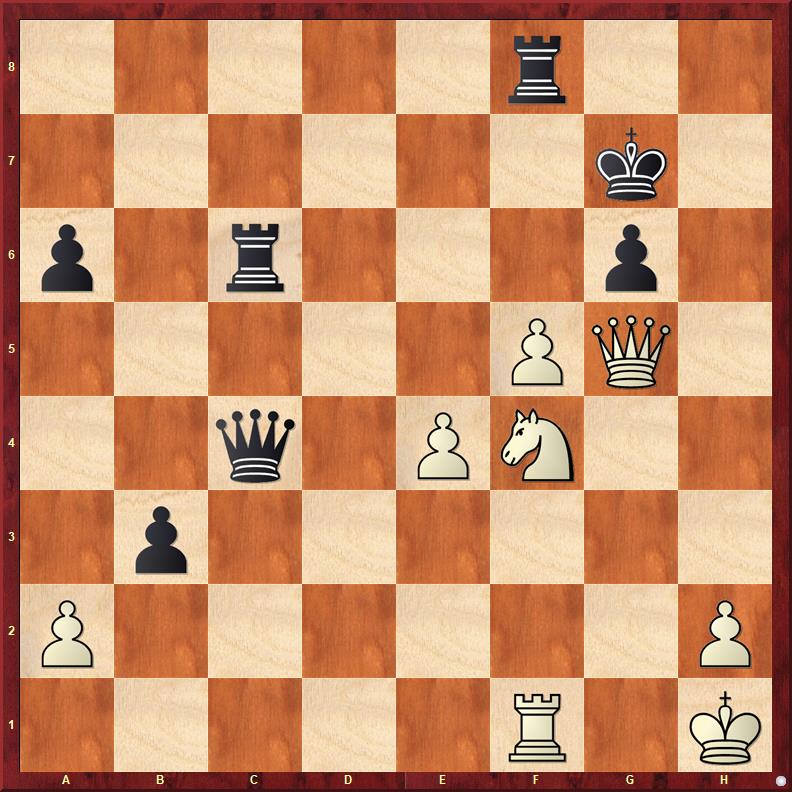

A key aspect of solving puzzles is broadening our perspective. In a position there are usually several possibilities – that is, candidate moves. The question is: do we always examine them or are we automatically looking for solutions without taking other important factors into consideration?

The answer, at least in my case, is often: no. Or more accurate: not enough. I notice a tendency to quickly steer my thinking toward a particular move. In this instance, my intuition told me:

37. Nh5+

But is this the only possibility? Of course not. White has two checks:

37. Nh5+ and 37. f6+

It is often wise to first consider the most forcing moves. The well-known order is:

- Checks

- Captures

- Threats

Before trying to select the best move, let’s take a moment to examine the position. This is wise because sometimes our intuition completely misleads us. For example, you might believe you see a certain pattern and act on it. Since you haven’t yet gained an overview of the entire position, you might overlook a simple opportunity to win a piece on another part of the board. I am deeply ashamed to admit it, but it has happened to me.

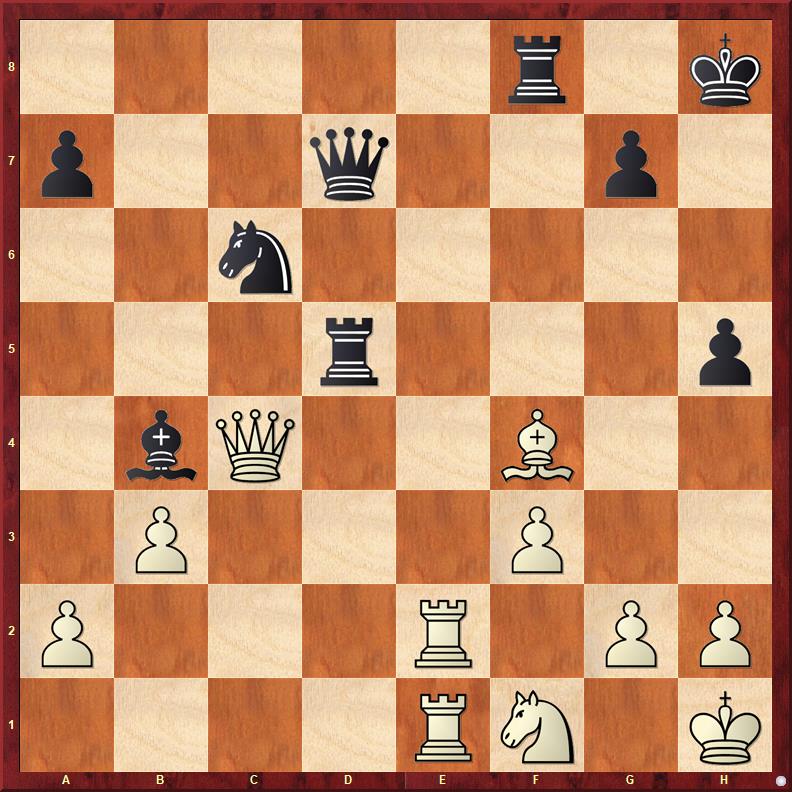

While solving puzzles it is not an ingrained habit to look first for the opponents threats. Basically one should always look for these threats first. In the position below (Capablanca – Kostic – Havanna 1919) black has two threats:

- Bxf1

- Rd4

The material balance is of course also very important. Therefore, another idea is to take a serious look at it. While solving puzzles, both are not ingrained habits. Too often I simply dive into the position because “I see something”. The outcome? I was searching for a tactical solution when the correct answer was relatively simple: white is up two pawns. Steering the game toward a winning endgame with 29. Re8 is the best solution. See the analysis here…

Back to the first position. Black had a material plus and he has a threat on the queen’s side. After b2 or bxa2, he is just one move away before the pawn can proudly be crowned to a queen. What about the safety of both kings?

Upon closer examination, neither king is safe. For example, Black can play Qxe4+ and even worse Qxf1+. But it is white to move. So, back to the possible candidate moves. My first thought was 37. Ph5+—but that leads nowhere. For example:

37. Ph5+ Kg8!

White has no good continuation. In other words: Black wins. Strangely enough, I initially hardly even considered:

37. f6+!

I stubbornly persisted in trying to make my dreamed-of candidate work. But I did not succeed. So, should I take a look at that other move? One reason to dismiss it was the pin along the f-file. And of course, because the f6-square is covered by three pieces (both rooks and the king).

37. f6+!

What I completely overlooked at first was that White can lure a piece to the f6 square and then simply capture it:

37. … Tfxf6 38. Ph5+

Now we’re on track! And the rest follows almost automatically.

What I learned from my mistakes?

First take enough time to study the position. Are there any threats? What’s the material balance? Which pieces are active? Are there loose pieces? Any checks or other forced continuations? Only then search for candidate moves and analyze them one by one. Most of the time you only need to calculate a few moves deep in each line. This case is no exception. Usually, after just a few moves it becomes clear whether a certain plan has a chance of success or not. View the analysis in your browser…

I found obth puzzles in “The Woordpecker Method” by Axel Smith and Hans Tikkanen. Also available as Chessable course.